第44回 国際シンポジウム

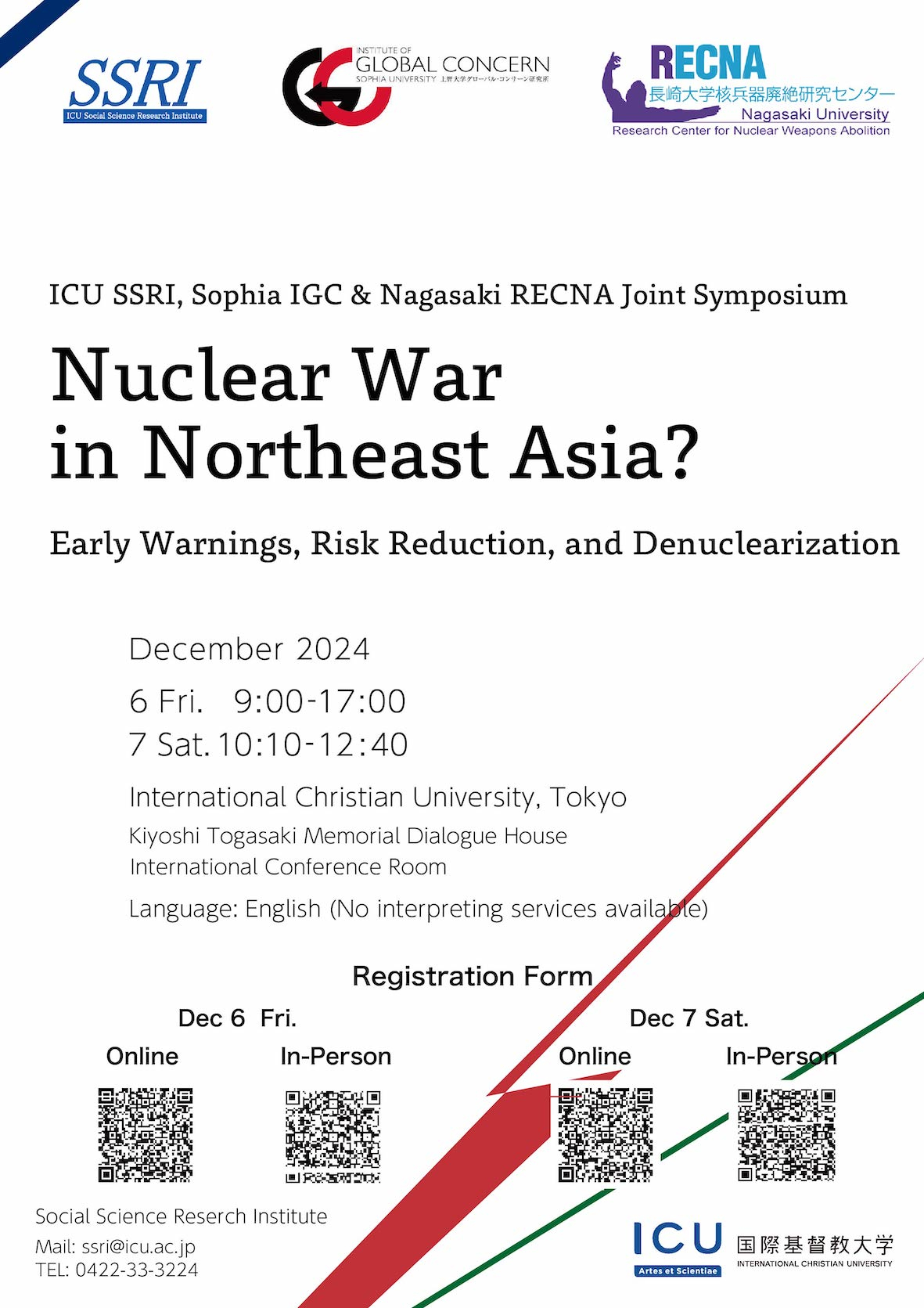

ICU SSRI, Sophia IGC, & Nagasaki RECNA Joint Symposium

"Nuclear War in Northeast Asia?: Early Warnings, Risk Reduction, and Denuclearization"

"Nuclear War in Northeast Asia?: Early Warnings, Risk Reduction, and Denuclearization"

Is Northeast Asia of the 21st century following the footsteps of Europe at the dawn of the 20th century? Just as major European leaders then believed "offense is the best defense" and tailored their military strategy to the belief, so the governments in Northeast Asia are racing to acquire the elusive pre-emptive capability that they believe will neutralize their adversary's offensive power before it is used. Just as the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand in Sarajevo in 1914 ignited the powder keg of Europe to explode into World War I, is an accident in the Taiwan Strait or the Korean Peninsula going to set off a complex chain reaction that no one can control and that may lead to an outcome no one desires? What are the measures that can be taken by governments and civil society in the region to prevent Northeast Asia’s future from degenerating into Europe’s past?

In 2022, North Korea’s legislative body took a bold, and highly destabilizing, step of legalizing a “nuclear first strike,” and Japan’s Kishida cabinet established in its security policy documents an equally destabilizing goal to pursue what it called the “counterattack capability” – the kind of military ability to strike enemy bases before they are used to launch an attack on Japan. The United States, which has long pursued its own version of the first strike capability, is “tailoring” its strategy to North Korea’s vulnerability and the changing military balance across the strait. Not only is China expanding its nuclear capability but also developing conventional capabilities that would overwhelm or neutralize missile defense systems being developed and deployed. While South Korea has been outspending the North on the military since the 1970s – by as much as 10 times in recent years – it has recently emphasized the imperative to develop the “3 axes system” that is designed to preemptively “kill” the North’s strike capability and “decapitate” its leadership. The symposium refines the concepts of “entangled security dilemma” and “enlarging security dilemma” to better understand these developments, which evidence the region-wide arms race toward the first strike capability and the dangers of an accidental war in the region.

What is to be done to prevent these developments from increasing tensions further and escalating to a war? The symposium explores possible measures that may be taken by civil society and governments in the Asia Pacific. It envisions three sets of interventions: diplomacy of reassurance, risk management and reduction, and a multilateral institution of comprehensive, common, cooperative security. First, the governments and civil society of the region may engage each other in a set of proactive diplomatic maneuvers to assure one another of their safety. Civil society actors may play the role of a monitor on the ground who senses early warning signs of trouble and alerts all relevant parties to the risks lest they should not get out of control. Second, the governments must adopt and implement a number of measures to manage and reduce the risks that the current postures may actually increase suspicions, tensions, and the likelihood of a war. These steps may include such arms control measures as hotlines and information transparency and such arms reduction measures as setting limits on the quantity of weapons systems and demobilizing certain military units. Finally, a stable institutional solution is required to transform the current state of instability into a situation of stability and peace. The entangled and enlarging nature of the region’s security dilemma calls for an institution of comprehensive, common, and cooperative (3 C’s) security in which a nuclear weapons-free zone of Northeast Asia may be embedded.

Language: English (No interpretation services available)

In 2022, North Korea’s legislative body took a bold, and highly destabilizing, step of legalizing a “nuclear first strike,” and Japan’s Kishida cabinet established in its security policy documents an equally destabilizing goal to pursue what it called the “counterattack capability” – the kind of military ability to strike enemy bases before they are used to launch an attack on Japan. The United States, which has long pursued its own version of the first strike capability, is “tailoring” its strategy to North Korea’s vulnerability and the changing military balance across the strait. Not only is China expanding its nuclear capability but also developing conventional capabilities that would overwhelm or neutralize missile defense systems being developed and deployed. While South Korea has been outspending the North on the military since the 1970s – by as much as 10 times in recent years – it has recently emphasized the imperative to develop the “3 axes system” that is designed to preemptively “kill” the North’s strike capability and “decapitate” its leadership. The symposium refines the concepts of “entangled security dilemma” and “enlarging security dilemma” to better understand these developments, which evidence the region-wide arms race toward the first strike capability and the dangers of an accidental war in the region.

What is to be done to prevent these developments from increasing tensions further and escalating to a war? The symposium explores possible measures that may be taken by civil society and governments in the Asia Pacific. It envisions three sets of interventions: diplomacy of reassurance, risk management and reduction, and a multilateral institution of comprehensive, common, cooperative security. First, the governments and civil society of the region may engage each other in a set of proactive diplomatic maneuvers to assure one another of their safety. Civil society actors may play the role of a monitor on the ground who senses early warning signs of trouble and alerts all relevant parties to the risks lest they should not get out of control. Second, the governments must adopt and implement a number of measures to manage and reduce the risks that the current postures may actually increase suspicions, tensions, and the likelihood of a war. These steps may include such arms control measures as hotlines and information transparency and such arms reduction measures as setting limits on the quantity of weapons systems and demobilizing certain military units. Finally, a stable institutional solution is required to transform the current state of instability into a situation of stability and peace. The entangled and enlarging nature of the region’s security dilemma calls for an institution of comprehensive, common, and cooperative (3 C’s) security in which a nuclear weapons-free zone of Northeast Asia may be embedded.

Language: English (No interpretation services available)